- If you forward your mail to Gmail, you probably aren’t seeing everything

- A lot of background

- An example of how this works

- What does this mean, and what should users do?

If you forward your mail to Gmail, you probably aren’t seeing everything

If you redirect or forward your email from your @jhu.edu address to another mailbox (maybe Gmail) and you believe (or know) that some email messages have disappeared, you are correct. This is intentional and by design of the sending organization (NSF, NIH, etc) — it is not a bug, and is not a problem that can be fixed. It is a protection, increasingly deployed across the internet, against the kind of spoofed emails that underly phishing attacks. The sending organization is telling Google not to trust email from its users that doesn’t come directly from its servers, and to delete that email because it isn’t authentic.

A lot of background

Historically, a portion of our community has redirected their @jhu.edu email address to another mailbox. Most often this was Gmail. While this wasn’t encouraged or supported by Johns Hopkins, WSE IT tried to take an impartial approach to this fact of life. We want people to use IT tools they’re productive and comfortable with and want to give people as many options as are practical. Users who configured their email to leave the JH border were accepting risk — we in WSE IT had limited ability to support them on Google’s services, and some of the security tools deployed by the IT@JH mail team would not be effective. WSE IT’s approach has been to try to get flexibility in the system for users who were willing to accept that risk, making room in the IT policy for people who wanted forwarding through Inbox rules and who needed SMTP access for message replies. We supported the use of multi-factor authentication tools to help ensure the JH border was secure in the face of the rise of phishing attacks, which were one of the primary arguments in favor of removing email forwarding. Most of the layers of email filtering for spam or harmful email were still in place for redirected email, though some tools (in particular, the ability to audit and delete phishing messages from user mailboxes) couldn’t be extended to mail that had left our systems.

Over time, this open stance has become problematic. The rollout of multi-factor authentication at JH and other sites — the major IT security initiative of the past several years — tightened the control of network borders, making stolen credentials less useful. It didn’t, however, address the flood of phishing, spear phishing, and ransomware / malware into email mailboxes. Stolen credentials weren’t required to send an email that appeared to be from someone at a user’s own institution or from someone the user knew personally, because the headers in email were very easy to fake and email servers would blindly move email based on the faked or obscured header information.

To address these issues organizations like NSF, NIH, Gmail, Microsoft, and Johns Hopkins, started to deploy a trio of new technologies:

- SPF, the Sender Policy Framework, which allows email domain owners to specify which servers are allowed to send mail from that domain

- DKIM, Domain Keys Identified Mail, a cryptographic authentication system that “signs” the header of an email message as authentic

- DMARC, Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting, and Conformance, which essentially is a way to publish the policy a sending organization wants to be followed when a received message fails the SPF or DKIM checks

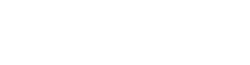

For example, SPF for the NSF.gov email domain looks like this (source):

It specifies which servers can send mail for users @nsf.gov. If a message using an @nsf.gov email address is received from a server not on that list then it should be considered falsified.

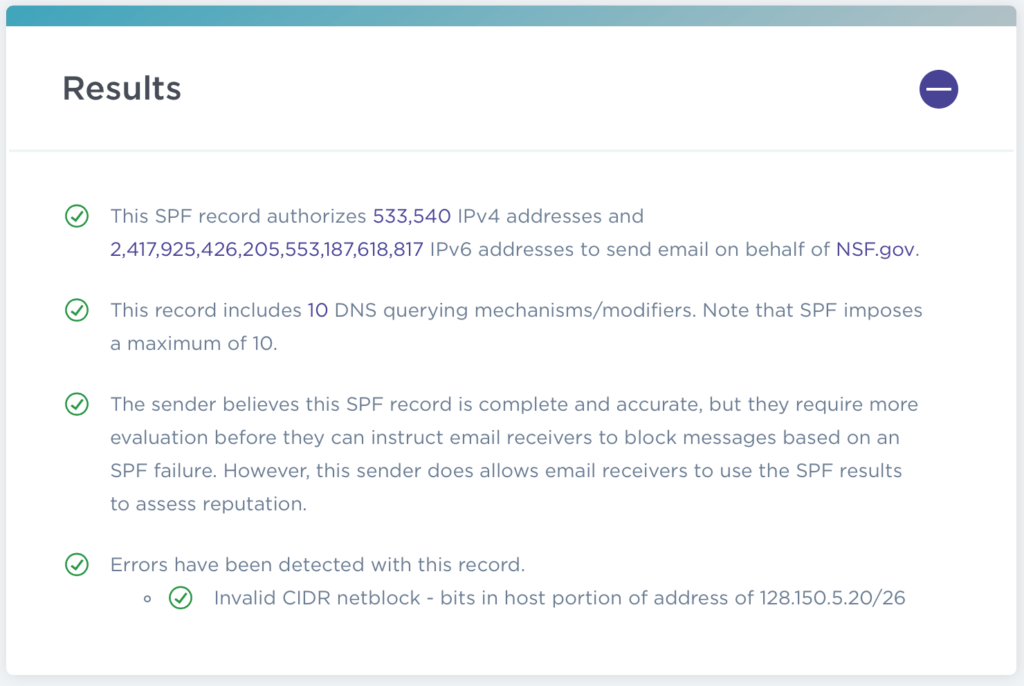

DMARC for NSF.gov looks like this (source):

The nsf.gov system administrators want 100% of inauthentic email to be rejected by the receiver (and want them logged back to NSF).

An example of how this works

Scenario: [email protected] sends a message to [email protected] and that message is redirected to [email protected]

- When redirected, it has been routed through JH and no longer originated from NSF’s servers. This is recorded in the headers.

- Gmail checks all incoming mail to see if the sender published a policy about what servers mail should come from (SPF). NSF does have that policy, and this message just failed that check.

- Gmail checks with the (at this point, presumably forged) sender about what to do with a message that flunks their checks (DMARC). NSF does have that policy, and that policy says the email should be rejected and not delivered.

- The system has worked as designed, but in this case has prevented a legitimate (though altered in the headers, and unexpectedly re-routed) message from getting through to the recipient.

For visual learners, you might be interested in trying the system at https://www.learndmarc.com/. It gives an animated version of how the email header information is parsed for DMARC.

What does this mean, and what should users do?

There is no cost to sending a malicious email, so millions and millions are sent every day. New approaches are constantly being tested and deployed by the adversary. Phishing and ransomware are real threats being directed at large organizations (including JH) every day. Given the nearly limitless ability for evil messages to be sent, the web of trust provided by tools like SPF, DKIM, and DMARC is one of the few ways to protect users. A time is quickly coming when domains that don’t use these tools won’t be trusted for email correspondence, as browsers no longer trust websites that don’t use HTTPS. This technology isn’t going to go away.

The effect of ignoring this situation is particularly harmful because you won’t know what you don’t get. A rejection message might go back into your @jhu.edu mailbox, if you have one, but if the intention was only to check mail @gmail it is unlikely that the JH mailbox is being closely monitored. You could maybe make a rule to handle specific VIP senders, but as this technology is implemented by more sites that position will become unworkable.

In the end, users should start using their JH mailboxes so they are sure they receive all their correspondence. In addition to being supported by WSE IT and the IT@JH mail team, the JH mailbox has many compelling features. WSE IT has a page detailing that here. [email protected] is available to help you transition from your old mail and calendar workflow to one based on the JH tools.